Moment of truth awaits Europe's Schiaparelli Mars probe

- Published

The European Space Agency (Esa) is getting ready to put a probe on Mars.

Its Schiaparelli robot will attempt the risky descent to the surface in the coming hours, after a 500 million km journey from Earth.

The touchdown is regarded as a dress rehearsal for a much more important venture in four years' time when Esa will bid to place a very expensive rover on the planet.

This six-wheeled vehicle will drill beneath the surface to search for life.

Getting the smaller Schiaparelli robot down ought to be the simpler affair. But as the scientific record shows, Mars is not the most welcoming of places, even for the most sophisticated of hardware.

About half of the missions despatched to Earth's near neighbour have failed. Many of these were lost on the way, missed their target, or crashed on arrival.

Schiaparelli's landing stages

Schiaparelli's landing sequence - stage by stage

For Europe, the Schiaparelli spacecraft is a chance to wipe away the disappointment of the Beagle-2 lander, which in 2003 got down successfully but then almost immediately suffered a terminal malfunction.

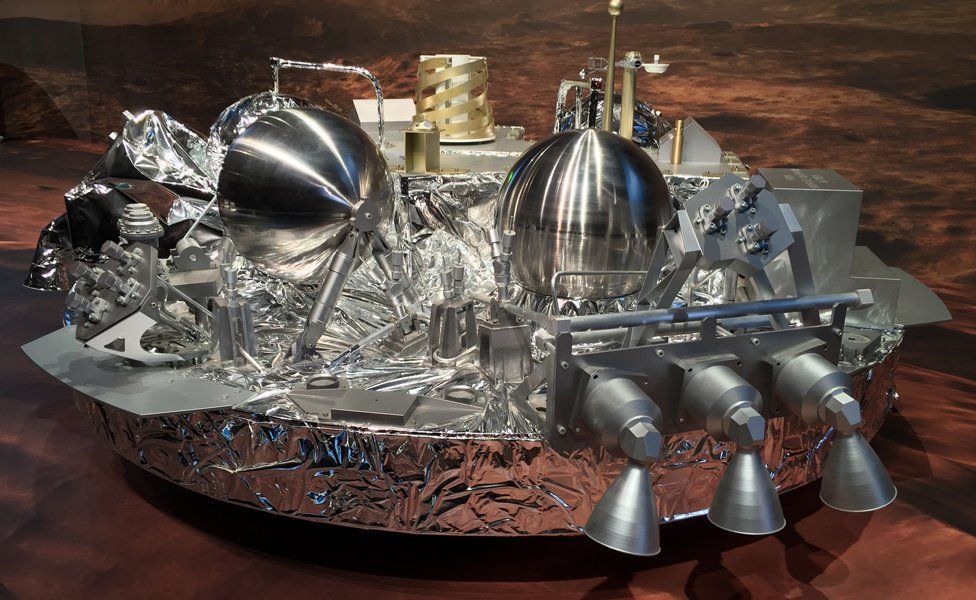

Schiaparelli will hope to fare better. It will use a combination of a heatshield, a parachute and a cluster of rockets to slow down its initial atmospheric entry speed of 21,000km/h to a hovering zero just above the surface.

The 600kg robot's final two metres will see it dump down on to its belly.

The Esa probe will emit UHF tones during the descent that an Indian radio telescope will try to capture and relay to controllers here in Darmstadt, Germany.

Touchdown should occur at 14:58 GMT (15:58 BST; 16:58 CEST). If the Indian facility can still hear Schiaparelli at the top of the hour, it will mean the Italian-built module must have reached the Martian terrain intact.

"Everybody's smiling, everybody's optimistic but you can sense the tension as well," said Mark McCaughrean, Esa's senior science advisor.

"I think as the hours tick by now towards that moment - to those six minutes as we plummet through the atmosphere - there's going to be a lot more nerves. But we're going to do this because it teaches us hard lessons about how to operate in space."

Some researchers like Colin Wilson from Oxford University will be experiencing the anxiety of 2003 all over again. He had a wind sensor on Beagle and he is flying it once more on Schiaparelli.

"It's nerve-wracking. I designed this instrument 14, 15 years ago and so it's been a long time waiting for this data. Then again, we know it's a high-risk game so we have to be involved in several missions," he told BBC News.

Schiaparelli will do some meteorological work for as long as its batteries remain charged. That should be a few days.

The science return may seem limited, but the probe is really geared towards technology demonstration. Assuming all goes well, the procedures used to get Schiaparelli down to the surface, together with some key elements of its hardware, will be copied for the mission to put a six-wheeled rover on Mars in 2021.

This solar-powered robot will spend several months drilling below the surface in a number of locations to search for the presence of microbial organisms.

"Long ago we started with industry to define the procedures and strategy for entering into Mars' atmosphere and trying to land successfully," explained Paolo Ferri, the head of mission operations at Esa's control centre in Darmstadt.

"It is all new for us. And going through this whole process, you gain enormous experience and expertise that will be very important and precious for the next landing attempt."

Colin Wilson: "The sensor is literally a build-to-print of the Beagle-2 design"

Both the 2016 landing and the 2021 project are part of Esa's so-called ExoMars programme.

This is a joint affair with Russia. Its space agency, Roscosmos, launched Schiaparelli and its mothership, the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) from Earth earlier this year. And it will do the same for the forthcoming rover. Russian scientists also have instrumentation spread across the different spacecraft.

While the media and public will of course focus on Schiaparelli on Wednesday, it is actually the TGO that represents the main interest for Esa this time around.

And at about the same time that the descent robot is trying to achieve its objective, the satellite will be taking up a parking orbit at Mars.

TGO plans to spend the coming years studying the behaviour of gases such as methane, water vapour and nitrogen dioxide in the Red Planet's atmosphere.

Although present in only small amounts, these components - methane in particular - hold clues about Mars' current state of activity. They may even hint at the existence of life.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos

- Published16 October 2016

- Published10 October 2016

- Published9 May 2016

- Published14 March 2016

- Published25 November 2015